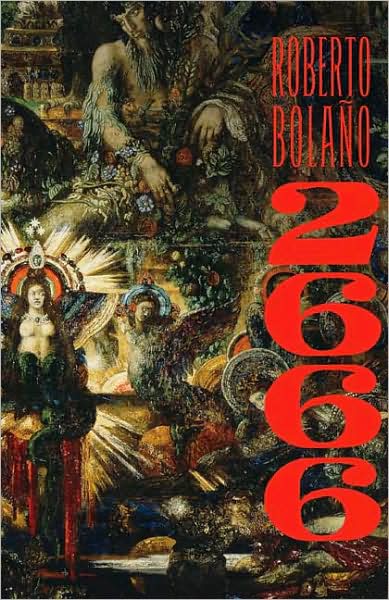

I'm reading Roberto Bolaño's 2666 with an online reading group. It's a very dense book, heavy in both senses of the word and I thought that a reading group would be helpful.

I'm reading Roberto Bolaño's 2666 with an online reading group. It's a very dense book, heavy in both senses of the word and I thought that a reading group would be helpful.It's a fantastic book, although I'm only 100 or so pages into it. It's a collection of five loosely-related "books." I'm mid-way through the first.

Anyway, as I was doing some reading online about Bolaño, I came across this quote, from Rodrigo Fresán’s eulogy of Bolaño (translated from Spanish):

I don’t know how there can be writers who still believe in literary immortality. I understand that there might be those who believe in the immortality of the soul, and I can even believe there are those who believe in Paradise and Hell and in that freaky intermediate station that is Purgatory, but when I hear a writer speak of the immortality of definite works of literature I feel like slapping him. I’m not talking about really belting, so much as just one slap, and afterwards, probably, hugging and comforting him. In this I know that you won’t be in agreement with me, Rodrigo, because you are basically a non-violent person. As am I. When I say, deliver a slap, I’m more thinking of the palliative character of certain slappings, like those in the movies that are administered to hysterics so that they will react, stop screaming, and save their own lives.It's such a nice quote, because it gets at what most writers aspire to--a type of literary immortality. Even those who imagine an granddaughter finding a dusty old box of journals in the back of the attic some day and pouring over them as if she has found, in the ramblings of her grandfather, an epic tale, humorous bits about a different time, the unpublished Great American Novel or, perhaps, just a bit of insight from someone who has seen more of life than she has.